|

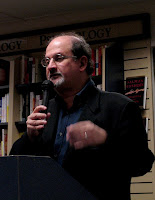

Salman Rushdie |

What is the relationship between the individual and society, between the microcosm and the macrocosm, between the solitary self and the great machinery of history? To phrase it more provocatively: do we shape history, or are we shaped—unmade even—by it? Are we, as rational agents, the masters of our age, or merely its casualties?

Saleem Sinai, the narrator of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, offers a paradoxical, almost comic answer. He asserts that everything that occurs in the vast, churning expanse of history happens because of him. That history—India’s partition, wars, elections, declarations of emergency—is his fault. It is a ludicrous claim, at once laughable and haunting, for behind its absurdity lies an uneasy question: what if the delusion of centrality is merely the tragic awareness of complicity?

Perhaps we are all, to borrow Saleem’s phrase, “handcuffed to history.” If this is true, then the burden of history is not merely placed upon us—we are, in fact, its architects. Thinkers as diverse as Jefferson, de Tocqueville, and Mencken have echoed the idea that people receive the government they deserve.

One might take this further: people receive the history they deserve. History is not a deterministic sequence carved in stone. It does not proceed along tramlines. It is not fate masquerading as chronology. It is, rather, a volatile, metamorphic consequence of human agency—of decisions made and deferred, of complicity, of silence. If history is not ours, whose is it? There is no other presence shaping it from beyond. There is only us.

These ruminations form the philosophical scaffolding of Midnight’s Children, a novel in which the personal and the political are inseparable. Saleem Sinai, born at the precise midnight of India’s independence, is more than a character; he is an allegory. He lives not just in history but as history. For him, the past is not a museum of events—it bleeds into the present, haunts it, animates it.

Contrary to some interpretations, Midnight’s Children is not a polemic against Islam. Like most of Rushdie’s works, it is steeped in Islamic culture, language, and metaphysics. In fact, it is Hinduism—and to some extent Christianity—that often emerges in a more critical light.

The portrayal of Islamic characters is rich, multidimensional, and deeply sympathetic. Saleem himself is the embodiment of Indo-Islamic cultural refinement, while Shiva—his mirror and rival—is cast in a more violent, carnal mould. The conflict between the two represents not only a personal rivalry but a broader commentary on culture, destiny, and the arbitrary lines drawn by history.

The prophecy delivered during Amina Sinai’s pregnancy is emblematic of the novel’s allegorical method: “There will be two heads—but you shall see only one—there will be knees and a nose, a nose and knees.”

What sounds like an ominous warning of monstrous birth is, in fact, a riddle about dual identity. Saleem and Shiva, born at the stroke of India’s independence, represent divergent fates switched at birth by the nurse Mary Pereira—an act as symbolic as it is literal. Saleem, though not of Aziz and Amina’s blood, is raised in wealth and privilege. Shiva, the true heir, is reared in poverty by a street musician. Fate is undone and rewritten by human intervention, much like history itself.

It is also significant that the major characters in Midnight’s Children are Muslim. The few prominent Hindu characters—Shiva (named after the god of destruction), Parvati-the-witch (a name invoking the goddess of fertility), and Padma Mangroli (named after the Ganges and Lakshmi)—are drawn in less flattering hues.

Though not caricatures, they are portrayed as lacking the cultural and intellectual refinement that marks Saleem’s world. Parvati, despite her magical gifts, cannot win Saleem’s affection and eventually turns to Shiva. Padma, who becomes Saleem’s final companion and the listener to his tale, is earthy, pragmatic, and stubbornly literal—perhaps a stand-in for the new India, practical and unsentimental, but also untutored in the complexities of memory and myth.

Yet, in Padma’s simplicity lies a kind of redemption. She anchors Saleem’s sprawling, self-referential narrative, much as the everyday anchors the epic. Through her, the story of one man—and one nation—becomes more than a metafictional experiment. It becomes a plea for witnesses. For remembrance. For accountability.

No comments:

Post a Comment