Where Indic wisdom meets global strategy. Reflections on culture, power, memory and the forces shaping civilizations past and present.

Pages

Sunday, December 31, 2023

When Law Forgets Dharma: Civilizational Crisis in Hindu Personal Jurisprudence

Saturday, December 30, 2023

Narendra Modi: In comparison to Thatcher, Xiaoping, Reagan and Gorbachev

|

Narendra Modi |

Monday, December 25, 2023

There are no good civilizations and evil civilizations

Saturday, December 23, 2023

The savage and the citizen: A philosophy of territory and property

Saturday, December 16, 2023

Two failed ideologies: socialism & capitalism

Sunday, December 10, 2023

Journalism: The Frightful Monstrosity and Delusion

“Journalism possesses in itself the potentiality of becoming one of the most frightful monstrosities and delusions that have ever cursed mankind. This horrible transformation will occur at the exact instant at which journalists realise that they can become an aristocracy.” ~ G. K. Chesterton, The New Priests (1901)

Chesterton wrote these words more than a century ago, but their prophetic resonance has only deepened with time. In the twenty-first century, we no longer live under the shadow of medieval churches or monarchs; our world is atheistic in temper and nihilistic in drift. Yet the collapse of older forms of authority has not left us freer. Instead, a new priesthood has arisen.

Its vestments are not of cassock and robe, but of camera and column. Its pulpits are not altars but television studios, newspaper pages, and social media feeds. Journalism has assumed the sacerdotal role—dispensing doctrines disguised as news, preaching sermons under the guise of analysis, shaping belief with the authority once reserved for religion.

Every day, the faithful are summoned to the liturgy of “breaking news.” Headlines blare like the bells of a cathedral, summoning the masses to attend to the latest revelation. The journalist speaks with the solemnity of a confessor and the certainty of a prophet. But unlike the old priests, who at least gestured toward eternal truths, today’s journalists traffic in shifting narratives, manufactured spectacles, and ideological dogmas. Their task is not to seek truth but to generate obedience; not to illuminate reality but to colonise perception.

The result is precisely what Chesterton foresaw: journalism has discovered its aristocratic vocation. It has become not the humble recorder of events but the maker of reality itself, declaring which facts are admissible and which must be exiled, which voices are worthy and which must be silenced. Under its dominion, pseudo-science masquerades as settled science, buffoons are canonised as intellectuals, and lies, repeated often enough, harden into the substance of collective memory.

Thus journalism, which once styled itself as the guardian of liberty, has become its usurper. It promised to speak truth to power, but it has become power; it promised to hold aristocracies accountable, but it has become the crooked aristocracy of our time. Its members sit not merely above governments and markets but above conscience itself, certain that their “narrative” is the final word.

Chesterton’s dire warning has been fulfilled. Journalism, unmoored from humility and truth, has indeed become a frightful monstrosity—a delusion more pervasive than any priestcraft of the past. It governs not by reasoned persuasion but by saturation, by the endless liturgy of the spectacle. And until it is dethroned from this aristocratic self-image, it will remain the most dangerous delusion of our age.

Saturday, December 9, 2023

Rama Rajya: The Civilization of Faith & Reason

Saturday, December 2, 2023

4 Most Powerful Geopolitical Forces in History of Civilization

Sunday, November 26, 2023

Life is not rational; reason is unknowable

Saturday, November 25, 2023

Self praise is a sign of weakness

Sunday, November 19, 2023

Bill Gates: The World’s Worst Book Reviewer

Saturday, November 18, 2023

Rereading Exodus by Leon Uris

Sunday, November 12, 2023

On Catherine Nixey’s book ‘The Darkening Age’

Saturday, November 11, 2023

Teaching of Bhagavad Gita: Dharma is superior to morality, ethics, legality

Sunday, November 5, 2023

The important lesson of history

|

Ruins of Nalanda University in Bihar (Started in the Vedic Age, before 1200 BCE) |

Sunday, October 29, 2023

Reason and morality are subjective, transitory and fallible

Saturday, October 28, 2023

Leftists are top capitalists; Rightists are incompetent capitalists

Sri Aurobindo: Gandhian politics, Tolstoyism and Bolshevism

|

Sri Aurobindo |

Tuesday, October 24, 2023

On Day of Vijayadashami: Four Mahavakyas from the Upanishads

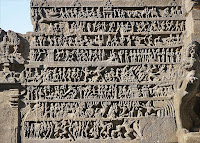

|

Rama story carved in wall of Shiva temple Ellora Caves, 8th Century |

Monday, October 23, 2023

Victor Hugo’s fallacious argument on ideas whose time has come

Saturday, October 21, 2023

Vishnu, the collectivist; Shiva, the individualist

|

Parvati and Dancing Shiva Ellora cave |

Sunday, October 15, 2023

The Frankensteins that America & Israel created in the 1980s

Saturday, October 14, 2023

Israel versus Palestine: The human quest for meaning

Sunday, October 8, 2023

Perfection is not possible; Lord Agni’s fire is enveloped in smoke

Saturday, October 7, 2023

Bhagavad Gita: Metaphysical and moral implications of the theory of rebirth, redeath

Tuesday, October 3, 2023

The Saptarshi in the asterism of the Big Dipper

Sunday, September 24, 2023

Rationality is a myth; man is a creature of emotions

|

Goddess Saraswati (10th century) |

Saturday, September 23, 2023

Lord Kalki: The end of metaphysics, the beginning of new universe

Sunday, September 17, 2023

John Galt: Ayn Rand’s world-destroying, world-conquering conquistador

John Galt, the central figure in Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, is often hailed as a prophet of radical individualism and the quintessential libertarian hero. But peel back the sheen of heroic rhetoric, and he emerges not as a liberator but as a postmodern conquistador—one who presides, not with sword and musket, but with monologues and manifestos, over the symbolic slaughter of millions and the systematic dismantling of civilization.

Galt is not a man of compromise. He believes he alone knows the optimal way of life, and in Rand’s telling, that conviction gives him the moral authority to impose his worldview upon all of humanity. His revolution is not merely ideological; it is cataclysmic. By the novel’s end, Galt and his disciples have crippled industry, toppled governments, sabotaged infrastructure, and watched—without flinching—as millions perish in the resulting chaos. This, we are told, is the necessary price of moral purification.

In Rand’s inverted moral universe, these orchestrators of collapse are not villains but saints. Their atrocities are justified, even celebrated, because they are carried out in the name of her so-called “rational” values: atheism, reason, individualism, unregulated capitalism, and freedom. That these values require the destruction of nearly everything else—tradition, community, religion, empathy, doubt—matters little. The world must be remade in their image, or it must burn.

This narrative impulse echoes Rand’s disturbing admiration for the historical conquistadors—men like Columbus and Cortés—whose genocidal violence, she believed, was a necessary prelude to the birth of modern America. In essays marked by staggering historical ignorance and moral blindness, she denigrated Native American cultures and suggested that their annihilation was deserved. Just as the conquistadors of old cleared the land with steel and fire, so too must Rand’s philosophical vanguard clear the mental and cultural terrain of the 20th century.

To be clear, Rand did not preach violence in the literal sense. But she recognized that her vision would never be accepted willingly. People, tethered as they are to religion, tradition, and emotional nuance, would need to be broken. And thus, Atlas Shrugged becomes not a novel of liberation, but of coercion through collapse. It is the fantasy of a cultural tabula rasa, achieved not by persuasion but by the erosion of everything else.

Galt does not kill with his hands. He kills with his voice. His infamous 60-page speech, the climactic sermon of Atlas Shrugged, is a rhetorical siege—a didactic ultimatum that offers no middle ground. Accept his truth in its totality, or be left to perish. The tone is not philosophical; it is theological. It is not a dialogue; it is dogma. In Rand’s Manichaean cosmos, there is no space for doubt, debate, or deviation. There is only the saved and the damned.

Though often labeled a philosopher of classical liberalism or libertarianism, Ayn Rand was no philosopher. Her grasp of the Western canon was shallow, her critiques of thinkers like Aristotle, Plato, and Kant riddled with caricature and confusion. Politically, she was less a theorist than a totalist—insisting that only one kind of person deserved to inherit the Earth: the person who lived strictly by her code. All others were unfit, parasitic, or tragically lost.

In the final decades of her life, Rand sought to birth a movement. What she managed instead was a cult. Her circle was filled with young, semi-educated idealists, many of whom soon grew disillusioned and abandoned her. Those who remained were often the mediocrities—the ones who mistook rigidity for clarity, bombast for brilliance. They lived in the shadow of Galt, and she became their oracle. Together, they transformed her system of thought into a theology without forgiveness.

Rand’s legacy endures not because of the strength of her ideas, but because of their allure. She offers certainty in a complex world, righteousness in the face of ambiguity, and a mythic hero for those weary of nuance. But beneath that promise lies a brutal message: if the world will not conform, let it collapse.

And in the end, that is what Atlas Shrugged is—a seductive hymn to destruction masquerading as liberation, a tale not of heroes but of zealots, not of freedom but of fire.

Sunday, September 10, 2023

Rajiv Malhotra's Being Different: Arguments against the ideologies of sameness, multiculturalism, assimilation

Sunday, January 8, 2023

Bhima: The Greatest Warrior of the Mahabharata

|

Raja Ravi Varma’s Painting of Bhima |