Where Indic wisdom meets global strategy. Reflections on culture, power, memory and the forces shaping civilizations past and present.

Pages

Wednesday, August 31, 2022

On Ganesha Vinayaka Chaturthi

Tuesday, August 30, 2022

The Lucifer Principle

Monday, August 29, 2022

The Terrorists Eat Their Own

|

Stallone with Afghan mujahideen In Rambo III |

Sunday, August 28, 2022

Petroleum: The Devil’s Excrement

|

First oil well in Saudi Arabia struck in March 1938 |

Saturday, August 27, 2022

When Jihad Was U.S. Strategy: The Forgotten Roots of Modern Extremism in Cold War Politics

|

Reagan with Afghan Mujahideen in the Oval Office (1983) |

Friday, August 26, 2022

The Battle of the Sexes: Patriarchy versus Feminism

|

Simone de Beauvoir |

Thursday, August 25, 2022

The Hindu Poet Who Wrote Pakistan’s First National Anthem

|

Jagan Nath Azad |

Wednesday, August 24, 2022

Mahatma Gandhi’s First Trip to Kashmir

|

Hari Singh in 1931 |

Tuesday, August 23, 2022

The Individual and the Infinite: Reflections on Midnight’s Children

|

Salman Rushdie |

Monday, August 22, 2022

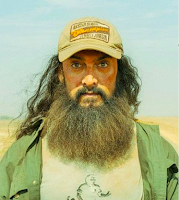

Pathaan: A Trailer, A Travesty, and A Triumph of Testosterone-Lite Cinema

In the interest of full disclosure—and because honesty is still a virtue in some circles—I must confess: I’ve only seen the trailer of Pathaan. That’s right, just the trailer. But rest assured, that was more than enough. I now feel spiritually qualified to not watch the film in its entirety. Why? Because sometimes, even a glimpse into the abyss is sufficient to comprehend its depth.

Let’s start with the title. Pathaan. A name that once evoked images of hardened warriors from the rugged mountains of Central Asia—men who carved empires with swords, not selfies. But in this cinematic rendition, the only thing being carved is Shah Rukh Khan’s dignity, courtesy of botox, pancake makeup, and a pair of CGI abs that deserve their own VFX team credit.

One might have expected a hint of Alauddin Khalji’s ruthless charisma. Instead, we’re served a bizarre hybrid of Mad Max meets Mumbai metrosexual—minus the madness and most certainly minus the masculinity. Shah Rukh, bless his high-cheekboned heart, tries to look menacing. What emerges instead is a character with the emotional depth of a hotel minibar and the menace of a scented candle.

The trailer, in its infinite generosity, offers us an orgy of car chases—none of which inspire awe, unless you're the sort who finds traffic jams thrilling. Clearly, someone in the production team was told, "Just make it look like Fast & Furious," and they responded, "What if Fast & Furious had no adrenaline and was edited on Microsoft PowerPoint?"

Then comes the romance. Enter Deepika Padukone: part femme fatale, part taxidermy experiment. Their chemistry is less smoldering and more smothering—a sort of emotional vacuum where passion goes to die. Watching Shah Rukh attempt seduction feels like watching a peacock try to waltz in a cement mixer.

John Abraham, meanwhile, floats through the trailer like a protein shake with eyebrows. He contributes nothing but a mildly constipated expression and the haunting sense that he was promised a different script. Together, he and Shah Rukh seem to be on a mission to normalize creepiness as an aesthetic.

But let’s not be naive. There is intent behind all this. Pathaan wants to make the Pathans seem cool. Not the historically accurate ones, mind you—the ones who razed cities, toppled dynasties, and considered plunder a weekend hobby. No, this is about the "woke Pathan": sensitive, shirtless, and possibly vegan. Shah Rukh would have us forget the delightful imperial adventures of the Khaljis, Lodis, Suris, and Durranis. Historical trauma? What trauma? Have a dance number.

And so, the trailer ends—mercifully. You’re left not exhilarated, but existential. You begin to question not just Bollywood, but the very trajectory of civilization. Was this the cultural zenith we were promised? Is this what centuries of subcontinental storytelling have led to?

The answer, dear reader, is no. Unless you are a wide-eyed devotee of Bollywoodian melodrama—unflinchingly loyal to the gospel of cringe—Pathaan will test your tolerance for mediocrity in high definition.

To sum it up: Pathaan is puerile, plastic, and profoundly pointless. A cinematic headache dressed as a high-octane thriller. It is, if the trailer is any guide, less a film and more a two-hour Instagram filter stitched together with bad lighting and worse dialogue.

You have been warned. #BoycottPathaan #ShahRukhKhan #CinemaDespair

Sunday, August 21, 2022

The Historic Blunder of 1937 & the Direct Action Day

|

Sarat Chandra Bose |

Saturday, August 20, 2022

The Date When the Muslims Became a Minority

|

Lt. Gen AAK Niazi signing the Instrument of Surrender |

Friday, August 19, 2022

On India’s Frog-in-the-well Foreign Policy

|

Modi and Netanyahu (July 2017) |

Thursday, August 18, 2022

Acharya Kripalani: On The Orgy of Violence in 1947

|

Acharya Kripalani and Sardar Patel |

Wednesday, August 17, 2022

Salman Rushdie’s Portrayal of Indira Gandhi

|

Feroze and Indira Gandhi |

Tuesday, August 16, 2022

The Communal Politics of Muhammad Iqbal

Monday, August 15, 2022

The Religion of Peace in Our Time

|

Peace dove statue Togo, Africa |

Sunday, August 14, 2022

When the Fatwa finds the West: Faith, freedom, and the long arm of history

It is, perhaps, unsurprising that the long shadow of the fatwa eventually found Salman Rushdie not in the East, where it was first proclaimed, but in the heart of the West—New York City.

The ironies of history often unfold in reverse: what once appeared as distant echoes from distant lands now resonate in the metropoles of modernity. The United States, long conceived as a bastion of secular liberalism, is increasingly encountering the paradoxes of pluralism, where the freedom to believe may inadvertently become the freedom to radicalize.

This tension forms the backdrop of Joel Richardson’s provocative 2009 work, The Islamic Antichrist, a text which explores the eschatological parallels between Christian and Islamic traditions. In the opening chapter, tellingly titled “Why This Book? Waking up to the Islamic Revival,” Richardson posits a future that many would have once dismissed as implausible: the potential Islamization of America by the mid-21st century.

Richardson cites demographic and sociological trends to support his thesis. Islam, he argues, has been expanding in the United States at a rate of approximately 4 percent annually, with some estimates suggesting that the figure may have doubled in recent years. Prior to 2001, it was reported that around 25,000 Americans converted to Islam each year—a figure that, according to certain Muslim clerics, may have quadrupled since the 9/11 attacks. That moment of national trauma, far from curbing curiosity or conversions, appears to have catalyzed a spiritual reorientation among segments of the population.

Geography, too, plays a role in this unfolding narrative. Richardson notes that urban America—its cities of commerce, learning, and cultural production—is where Islam’s new adherents are most concentrated. The greater Chicago area, he observes, is home to over 350,000 Muslims, while New York City’s Muslim population surpasses 700,000. These numbers, while modest in relation to total populations, point to deeper undercurrents—of migration, identity-seeking, and ideological flux.

Yet it is not mere numbers that concern Richardson, but the character of the conversions. He expresses alarm at the possibility that some new adherents are being drawn not just to the spiritual dimensions of Islam, but to its more militant or political interpretations. He claims that elite American universities, progressive as they are in self-image, may unwittingly serve as fertile ground for radical thought—alongside certain urban mosques, which mirror the ideological ferment of madrasas in the non-Western world. In his view, the crisis is not confined to the peripheries of failed states; it is incubating within the very institutions that once prided themselves on their Enlightenment heritage.

Richardson extends his gaze to Western Europe, identifying similar patterns of growth and ideological fragmentation. Across France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, he sees not a seamless integration of communities but a fracturing of secular consensus. The question he raises—though not without controversy—is whether the liberal state, in its earnest attempt to protect religious expression, may have underestimated the transformative power of belief systems that carry their own political theologies.

To reflect on these matters is not to indict Islam or its followers wholesale. It is, rather, to grapple with a deeper philosophical question: can modern secular democracies accommodate faith traditions whose ultimate vision of society may not be secular? Where does tolerance end and complicity begin? And is it possible, in a world increasingly shaped by transnational flows of belief, identity, and grievance, to uphold both freedom of religion and freedom from religious coercion?

The attack on Rushdie—decades after The Satanic Verses and far from the lands where his book was first banned—serves as a somber reminder that ideas, like their authors, travel. And sometimes, so do the forces that seek to silence them.

Saturday, August 13, 2022

The Fatwa Catches Up With Salman Rushdie

Truschke’s Rewriting of Aurangzeb: Between Apologia and Amnesia

|

Kashi Vishwanatha Temple |

Thursday, August 11, 2022

Laal Singh Chaddha: A Flop of Forrest Gumpian Proportions

|

Aamir as Laal Singh Chaddha |

Wednesday, August 10, 2022

V. D. Savarkar On Mahatma Gandhi’s Politics

|

V. D. Savarkar |

Tuesday, August 9, 2022

The invader’s triumph, the culture’s survival

|

Descent of Ganga |

“Cultures don't survive, cockroaches do. The second we stopped being cockroaches, the whole species went extinct.”

“Civilization is just a lie we tell ourselves to justify our real purpose. We're not here to transcend. We're here to destroy.”

— William to his host doppelgänger, Westworld, Season 4, Episode 7

William’s words drip with cynicism and nihilism, yet they contain a shard of historical truth. History often appears to vindicate the destroyers rather than the creators. Civilizations that cultivated art, philosophy, and refinement have, more often than not, been overrun by those who knew only the brutal grammar of conquest. The invader’s sword can, in a season, undo the work of centuries; the plunderer’s greed can reduce temples, libraries, and entire cities to dust.

In the seventh century, when Islam arrived in South Asia, the subcontinent was home to some 400 million souls—an astonishing 56 percent of the world’s population. By the eighteenth century, after centuries of invasions, internal upheavals, and the long shadow of the Mughal decline, the number had fallen to around 140 million. These figures, drawn from Wikipedia’s Demographics of India page, speak of a staggering loss—nearly 65 percent of the population gone.

This was not a mere statistical fluctuation; it was a civilizational trauma. Wars and riots, famine and disease, political persecution, lawlessness, and the unrecorded toll of despair and psychological ruin—together, they carved deep wounds into the body of society. And yet, despite the relentless assault, the ancient religious traditions of the land—Hinduism above all—endured. It survived not because its adherents were immune to suffering, but because they refused to surrender their identity, even under the most brutal of trials.

The painting I have chosen to accompany this piece—Raja Ravi Varma’s Descent of Ganga (1890)—is not directly related to the subject. Yet it feels appropriate: a vision of sacred continuity, of a river that flows on, bearing with it the memory of civilizations that may bend but do not break.

Monday, August 8, 2022

Jadunath Sarkar’s History and the Truth About the Mughals

|

Jadunath Sarkar |

Sunday, August 7, 2022

The Profound Revolution: The Battle of Plassey

|

1762 painting of Clive meeting Mir Jafar after the Battle of Plassey |